Malaysia is hot. Not only hot, but sticky, due to the high humidity associated with a tropical climate. Go for a training run, or take part in a race and these conditions routinely slow us down, making us feel pretty awful in the process. Consequently, many of us do what we can to help beat the heat, running early in the morning or late evening, wearing minimal clothing, as well as drinking lots before and/or during the run. But what more can you do to help endurance running in the heat?

This was the fundamental question that our research set out to answer. We conducted research into a range of different interventions, seeking to assess not only their effectiveness for running in the heat, but also to better understand how these interventions influence our bodies.

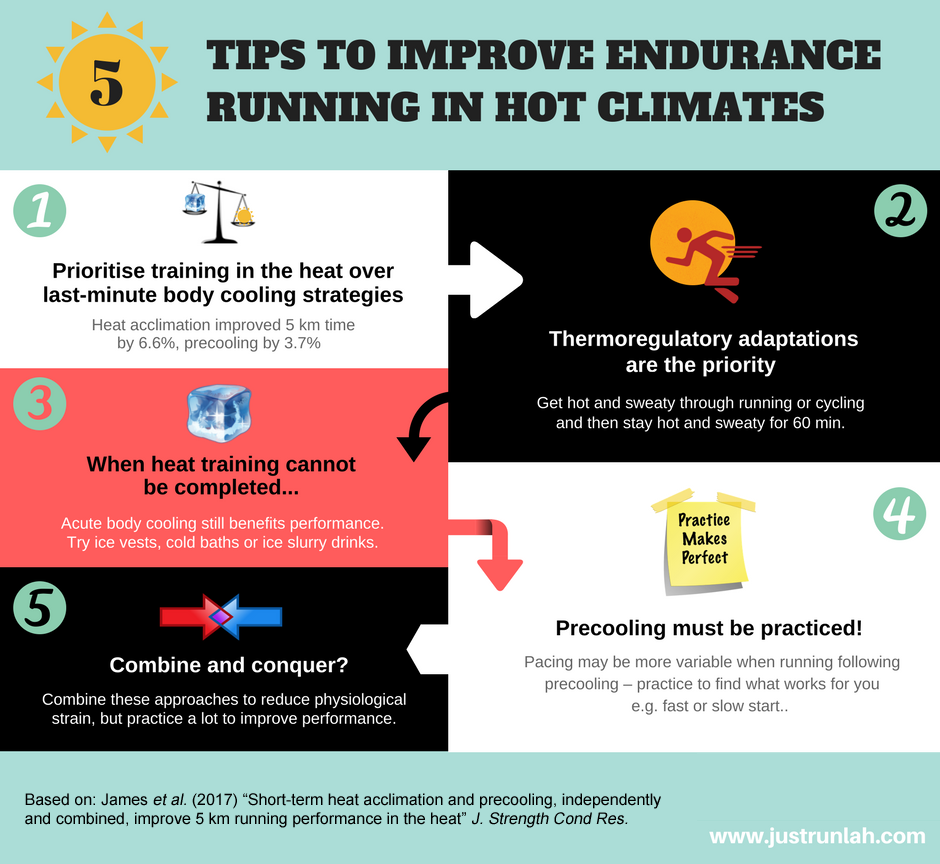

Broadly, your preparation for competing in the heat boils down to two choices; 1) repeatedly train in the heat to allow your body to adapt or 2) in the hour before competing, cool yourself down as much as possible through cold (iced) clothing, cold drinks or partial cold water immersion.

Analyses of all of the research that has taken place on these topics, shows both (acute) precooling and (chronic) heat adaptation, to be beneficial, if you are going to run in the heat. The latter is commonly termed ‘heat acclimation’, when adaptation occurs within an artificially hot environment (e.g. heat chamber/sauna), or ‘heat acclimatisation’ when adaptation is achieved with a naturally hot environment (e.g. outside in the tropics).

Heat acclimation elicits adaptations that include a lower resting and exercising body temperature, improved sweat response and an increased blood volume. This helps us to lose heat quicker as we run, reducing the strain on the body and sensations of well, awfulness.

Notable examples of precooling include the use of cold water baths and ice ‘slurry’ drinks before running, or wearing multiple cooling garments. On the longer-term, acclimation side of the fence, 4 days, 5 days, 8 days and 10 days of training in the heat all appear beneficial. Social media permits insights into top athletes adopting a variety of these practices, as they juggle the convenience of a short term solution (IAAF ice vests) versus a longer-term preparation (Jonny Brownlee heat training), with their competition & travel schedules.

Despite this apparent age-old conundrum, these approaches have not previously been compared to tell us how best to prepare for running in the heat. We might expect the longer-term solution to be more beneficial, as this involves the body adapting to the heat, versus temporary cooling. But no-one knows if this is the case, or indeed how big this difference may be. Moreover, these techniques have never been combined – could you gain a greater performance benefit from doing more?

To answer these questions we recruited local, competitive runners to complete four, 5 km treadmill time trials in the Environmental Extremes Laboratory at the University of Brighton, England, with conditions set to 32°C and 60% relative humidity, not unlike the daily conditions here in Malaysia.

The first trial was either a control trial, where runners prepared as normal or a precooling trial. This began after 20 minutes of wearing an ice vest, adorning wet & iced towels around the head and neck, plunging hands and forearms in cold (9°C) water and wearing shorts filled with ice packs.

The third and fourth trials followed five days of training in the heat, each for 90 minutes, to heat acclimate. This was achieved through ‘controlled hyperthermia’, whereby participants exercised (cycled) hard for 30 minutes to increase their core temperature above 38.5°C and then predominantly rested for the following hour, exercising for 5 min occasionally, to maintain core temperature >38.5°C. Once heat acclimated, runners completed the 5 km without any further intervention, or with precooling runners once acclimated.

Once all the trials were completed we found that precooling improved 5 km time by 3.7% compared with the control trial, whilst heat acclimation improved performance by 6.6% and combining these provided a 7% improvement.

So it appears that we should prioritise training in the heat over last minute cooling. Interestingly, when precooling was added once runners were heat acclimated, measures such as heart rate and skin temperature indicated runners were under less physiological strain, but this did not transfer to faster running. Based on the runner’s feedback and analysis of their split times, we believe they didn’t know how to pace themselves optimally, as they probably didn’t know their ‘new’ limits, following both precooling and heat acclimation. Therefore, if they practiced a lot more with cooling or once adapted, including fast/slow/moderate starts, it’s very possible we may have seen larger improvements when the two approaches are combined.

The complete article of this study can be found here, in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

In summary, if you train in the heat this is likely to benefit performance more than cooling just before you run or race. However, if this isn’t possible, cooling still appears to help performance in the heat – so give it a try. Finally, if you do try cooling, either on it’s own or following some consecutive days of training in the heat, be sure to practice at race pace so that you can maximise the benefits.

Quick win:

Try a cold bath (>10 min) before you next run outside.